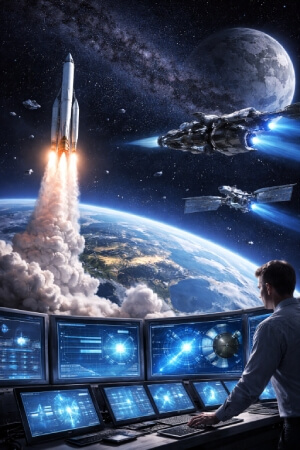

Propulsion Systems and the Challenge of Leaving Earth

Propulsion is one of the paramounts of any space mission. Without controlled thrust, there is no chance for the spacecraft ever to escape the clutches of the earth under the force of gravity, to go from one orbit to another, or to follow a true trajectory, even though the spacecraft can eventually rely on planetary gravity to propel it into a trajectory. Engineers treat propulsion systems as a combined physics and reliability problem since any malfunction will end the mission in seconds.

Thrust Generation and Energy Conversion

At its core, propulsion relies on converting stored energy into motion. Chemical systems release energy through controlled reactions, producing high thrust over short periods. Other approaches favor efficiency over raw power, allowing gradual acceleration over long durations. Engineers select methods based on mission timelines, payload mass, and available energy sources.

The challenge lies in controlling this energy precisely. Even minor variations in thrust can alter trajectories across millions of kilometers. Extensive modeling ensures that engines behave predictably under varying conditions.

Reliability and Redundancy in Engine Design

Propulsion components face extreme stress, including vibration, heat, and pressure changes. Engineers build redundancy into critical elements so that a single failure does not immediately compromise the mission. Valves, sensors, and control software are often duplicated or cross checked.

Testing propulsion systems on Earth requires simulating conditions that cannot be fully replicated. Engineers use vacuum chambers, thermal cycling, and accelerated wear tests to uncover weaknesses before launch.

Trajectory Planning and Course Corrections

Propulsion is not only about launch. Small adjustments during flight correct deviations caused by gravitational influences and minor errors. These maneuvers must be carefully timed and calculated to conserve fuel while maintaining accuracy.

Engineers integrate propulsion planning with navigation models, ensuring that thrust events align with orbital mechanics rather than fighting them.

Mobility Systems for Surfaces Beyond Earth

One cannot say that once a spacecraft traverses great distances, its journey has now ended; land-based mobility systems are developed to enable exploration, construction, and support in environments vastly different from Earth's. Design decisions in this case are made with low gravity, abrasive dust, and rough terrain in mind. These highly autonomous mobility systems are required to stand on their own for long periods of time, even without human intervention. This is intended to ensure that durability, adaptability, and simplicity are reflected in their design.

Adapting to Reduced Gravity

Lower gravity changes how vehicles interact with the ground. Wheels, legs, and suspension systems must maintain traction without relying on weight alone. Engineers study soil mechanics in reduced gravity to predict how surfaces will respond to movement.

Designs often emphasize wide contact areas and flexible structures that distribute forces evenly. This helps prevent sinking or slipping on loosely compacted surfaces.

Mechanical Simplicity and Durability

Complex mechanisms are harder to repair when maintenance opportunities are limited. Engineers favor designs with fewer moving parts and minimal reliance on lubrication, which can behave unpredictably in extreme temperatures.

Materials are selected for resistance to abrasion and thermal cycling. Dust infiltration is a constant concern, as fine particles can damage joints and seals over time.

Autonomous Navigation on Alien Terrain

Surface mobility systems increasingly rely on onboard autonomy. Cameras, sensors, and algorithms allow vehicles to assess terrain and choose safe paths without constant guidance from Earth.

Communication delays make real time control impractical. Engineers design systems that can pause, reassess, and adapt when unexpected obstacles appear.

Navigation and Guidance Across Vast Distances

Looking through a larger part of the galaxy is more germane than just following some flight paths. Precisely setting up how much the load is moved off halfway in such a long time, as well as its behavior with respect to the particular forces that partly alter its path, becomes crucial. The navigation systems engage mathematics, sensing, and the existing communication infrastructure. Together they continuously build the ship's state in coordinates and attitudes with respect to the state coordinates implied by the inertial sensors and primary navigation.

Inertial Measurement and Reference Frames

Spacecraft rely on inertial measurement units to track motion without external references. These systems use gyroscopes and accelerometers to calculate changes in velocity and orientation.

Over time, small errors accumulate. Engineers correct them by periodically referencing known objects or signals, maintaining alignment with established coordinate systems.

Celestial and Signal Based Positioning

Stars, planets, and artificial signals provide reference points for navigation. By measuring angles or signal delays, spacecraft can refine their position estimates.

These methods require precise timing and calibration. Engineers account for signal travel time and relativistic effects, especially during high speed or long distance missions.

Autonomy and Fault Tolerance

Navigation systems must continue operating even if sensors degrade or fail. Engineers design software that can cross validate data from multiple sources and identify anomalies.

Autonomous fault handling allows spacecraft to maintain orientation and trajectory long enough for engineers on Earth to respond.

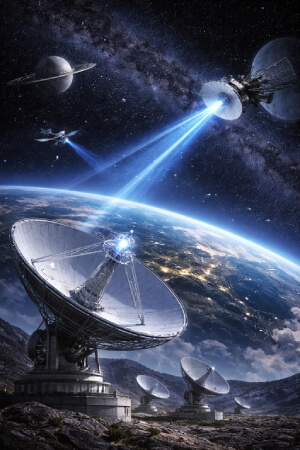

Communication Systems in Extreme Isolation

Communication between space and the Earth is important; it includes activities like control, data transmission, and situational awareness. As missions go deeper into space, communication becomes really tough for some reasons. The design of the communication systems must take weak signals with long delays due to the time taken for the signal's reach and maintenance of power sources into consideration. These design constraints also influence aspects of technology such as antenna design or data rate compression.

Signal Transmission and Reception

Transmitting data across vast distances requires precise alignment and amplification. Antennas must be accurately pointed, often while the spacecraft itself is moving or rotating.

Engineers balance transmission power against energy availability. Efficient modulation techniques help maximize information transfer without exhausting onboard resources.

Managing Delays and Interruptions

Communication delays mean that instructions sent from Earth arrive minutes or hours later. Systems must operate safely during these gaps, following pre programmed behaviors.

Temporary signal loss is expected. Engineers ensure that spacecraft can store data and resume communication without data corruption once contact is restored.

Data Prioritization and Integrity

Not all data is equally important. Engineers design systems that prioritize critical health and status information over less urgent scientific data.

Error detection and correction techniques protect information from noise and interference. This ensures that received data remains usable despite transmission challenges.

Life Support and Environmental Control Systems

Survival systems sustain human life in environments that offer none of the necessities found on Earth. They regulate air, water, temperature, and pressure within tightly controlled limits.

These systems must operate continuously and predictably. Even brief interruptions can pose serious risks, making reliability a primary design objective.

Atmosphere Management and Recycling

Life support systems control oxygen levels, remove carbon dioxide, and filter contaminants. Recycling is essential, as resupply opportunities are limited or nonexistent.

Engineers design closed loop systems that minimize waste and recover usable resources. Extensive testing ensures stable operation over long durations.

Thermal Regulation in Harsh Conditions

Temperature extremes are common beyond Earth. Systems must manage heat generated by equipment while protecting occupants from external cold or heat.

Thermal control combines insulation, radiators, and active regulation. Engineers simulate worst case scenarios to ensure stability under varying conditions.

Psychological and Human Factors

Survival extends beyond physical needs. Engineers consider lighting, noise levels, and spatial layout to support mental well being.

Designs aim to reduce stress and fatigue, recognizing that human performance affects overall mission success.

System Integration and Tradeoff Management

No system operates in isolation. Spacecraft are networks of interdependent components, each affecting the others. Integration is the process of making these elements function as a coherent whole.

Engineers manage tradeoffs between mass, power, complexity, and reliability. Decisions in one area often impose constraints in another.

Balancing Mass and Performance

Every kilogram added to a spacecraft increases launch costs and affects propulsion requirements. Engineers scrutinize designs to eliminate unnecessary weight.

Lightweight materials and multifunctional components help reduce mass without sacrificing capability.

Power Distribution and Resource Sharing

Power systems supply energy to all onboard systems. Engineers design distribution networks that allocate power efficiently and prioritize critical functions.

Shared resources require careful coordination. Conflicts are resolved through scheduling and automated management.

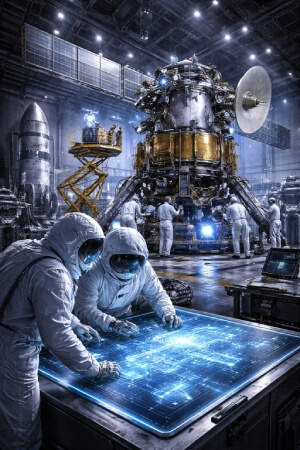

Testing Integrated Systems

Testing verifies that systems interact as expected. Engineers conduct integrated simulations that replicate mission timelines and environmental conditions.

Failures discovered during testing inform design revisions, improving robustness before deployment.

Engineering for Hostile Environments

Space missions subject systems to radiation, vacuum, temperature extremes, and micrometeoroids. Designing for these conditions involves the use of materials and strategies to protect. Engineers anticipate degradation in the components due to the time factor. The design anticipates the loss of competence over a given system while accommodating functions considered essential.

Radiation Hardening and Shielding

Radiation can damage electronics and materials. Engineers select components that tolerate exposure and add shielding where feasible.

Software also plays a role, detecting and correcting errors caused by radiation induced disruptions.

Vacuum and Pressure Challenges

In vacuum, materials behave differently. Outgassing, thermal expansion, and lubrication issues can affect performance.

Engineers test components in simulated vacuum environments to identify and mitigate these effects.

Designing for Long Term Degradation

Systems are built with margins that allow continued operation as components age. Predictive models estimate wear and guide maintenance strategies.

This approach supports missions that operate for years without direct intervention.

Testing, Validation, and Iterative Design

The process of testing prior to deployment is intense in nature. The main problems are discovered early, enabling corrections to be made while the systems are still at their desired status. Testing, as such, is actually an ongoing process- efforts to optimize and validate these new designs are performed at each stage.

Simulating Space Conditions on Earth

Facilities replicate vacuum, temperature extremes, and radiation exposure. While no test environment is perfect, combined methods approximate real conditions.

Data from these tests inform adjustments to materials, software, and procedures.

Incremental Development and Prototyping

Prototypes allow engineers to evaluate concepts before committing to final designs. Incremental development reduces risk by validating assumptions step by step.

Lessons learned from earlier iterations shape later improvements.

Building Pathways Into the Unknown

The process of moving beyond Earth is thoughtfully reasoned and meticulously articulated. Each system reflects careful consideration for risk, the environment, and human needs. Together, these systems form the invisible infrastructure of exploration. By focusing on integration, testing, and adaptability, engineers develop the pathways for safe and sustainable progressing through even the most hostile environments.